25 Feb Teaching Digital Hygiene

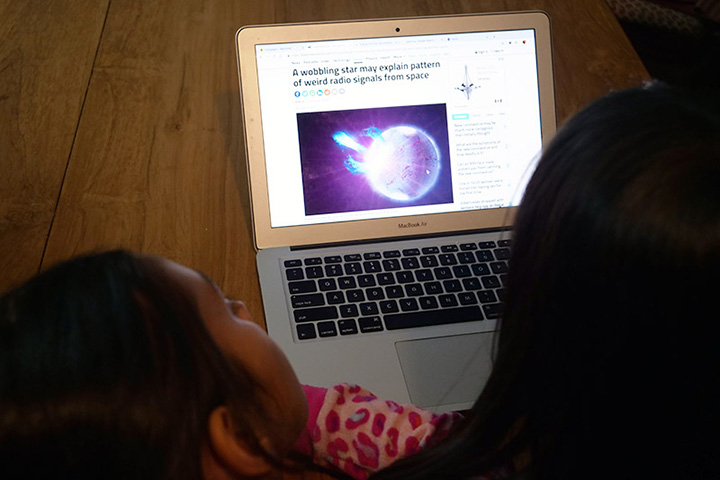

Our Middle Years students are just getting to the end of device-free week. It’s fair to say this is not the most eagerly awaited event on the school calendar.

These kids are digital natives. While many of us have had to adapt to this new era, Middle Years students are the first generation to be born since the launch of the first-generation iPhone. They have never known anything else. Let’s face it, the internet is amazing, and if you’ve grown up knowing nothing else, resistance to ‘screen-time’ could be seen as naïve, archaic, counter-intuitive.

"Access to knowledge has never been easier. So, is device-free week the digital equivalent of locking students out of the library?"

Today’s connectivity, the vast virtually unlimited knowledge sharing potential of the internet, is the most powerful tool for humanity’s collective intelligence since the printing press. Scientists and scholars can collaborate with their peers around the world. Students can access academic material the likes of which would be unimaginable within the constraints of a physical library. This technological connectivity has increased the educational gene pool, much as the bicycle is credited with growing the literal gene pool in Europe in the nineteenth century. No matter how obscure, if you’re interested in a particular area of study, there will be someone who is further down the road than you, whose work you can learn from and build on. And they’re only a few taps of a keyboard away. They probably have their own blog or YouTube channel. Access to knowledge has never been easier.

So, is device-free week the digital equivalent of locking students out of the library for a week? No. Because for all the amazing, mind-expanding material the digital world holds, there’s an awful lot of junk. And junk content, like junk food, can be hugely satisfying on consumption, and in moderation can be a good thing, but is unhealthy when it constitutes too much of your diet. “Expecting the social media companies to regulate themselves is like expecting a Labrador (dog) to regulate itself in a hammock full of sausages,” said comedian and author Andy Zaltzman recently. The same analogy can be applied to our children. Given free choice between wholesome, challenging content which expands our knowledge, and gorging themselves on light-hearted fun, it’s no surprise that many children (and adults) will opt for the empty calories.

Another issue with screens is how they affect the way we interact with each other. All of us have probably spent a significant part of all our lives in front of screens of one sort or another. The difference is the omni-presence of today’s devices. Had you brought a portable TV, or even a book, to the dinner table twenty years ago, you would have been seen as eccentric at best. Now it can be disheartening to see a group of students, or adults, sitting around a table, staring into screens rather than engaging in meaningful interaction with each other. The reality is that most of the time this isn’t huge a problem, but for some students who are shy or struggle socially, retreat into the digital world can be an easy way out, a barrier to developing their social skills and sense of self.

"How, as parents and educators, do we deal with this paradox which on the one hand offers both an intellectual utopia and on the other an unending escape from meaningful thought?"

A further real concern from parents on the downside of screen-time is its addictive and distracting quality. Recent research out of Harvard University showed that even having a phone in your pocket or on your desk resulted in a small but statistically significant impairment of an individual’s cognitive abilities. The effect remained true even if the phones were turned off. Why? FOMO – fear of missing out. As humans, we are pre-programmed to pay attention to things that are relevant to us. As the Harvard Business Review put it, “the mere presence of our smartphones is like the sound of our names — they are constantly calling to us, exerting a gravitational pull on our attention.”

So how, as parents and educators, do we deal with this paradox which on the one hand offers both an intellectual utopia and on the other an unending escape from meaningful thought? One thing history has shown is that where prohibition fails, prescriptive approaches are a more helpful learning model. The latter allow for moderation and modulating of use depending on the context and it also works against seeing these things as ‘forbidden fruit’ that in the end can lead to overconsumption. This may seem slightly ironic given the prohibitory nature of device-free week. But for children who have never known a device-free world to spend a week or two experiencing what real life beyond the screen can offer is not a bad thing.

New York University’s Adam Alter puts our responsibility as parents and educators on par with basics like teaching our children how to brush their teeth, how to interact, and teaching them manners. “I think one of the things parents and schools should teach kids is sort of technological hygiene. How do you interact in the world with screens? How do you act in a way that is good for you, good for the people you’re interacting with, that it that maintains your integrity, that means you have time for other things? That’s not being taught, but I think it’s a really critical new life skill that we didn’t have to worry about 20 years ago.”

This generation will grow up entwined with technology in ways that we can only yet hope to understand. As access to knowledge becomes easier, the ability to process and meaningfully interpret that data becomes predominant. Ultimately, all we can do, as parents and educators, is to teach children to be aware of the great potential and downfalls of the internet, be mindful and conscious of their consumption, to develop healthy online habits – essentially show them how to brush their digital teeth.

Dr Craig Cook, Principal, Woodstock School

Peggy Naumann, '74

Posted at 05:12h, 16 MarchI’m so glad to see Woodstock doing this. It’s really important.